The possibilities of misreading lurk at every corner when dealing with new literatures – for example, we could be seeking elaborate cultural contexts for texts by Aboriginal authors that do not explicitly use Aboriginal knowledges. This is a problem that every reader of culturally different texts faces. Native American scholar Louis Owens has questioned whether, in the face of the political inequality within colonized space, it is inevitable that when the Aboriginal text is read at the transcultural frontier what may result may be ‘mere surface appropriation only, a shadow borrowing and simulacrum of tribal culture.’ The question is relevant not only to non-Native readers within Australia and Canada, but also for us Indian readers working well outside the immediate political context in which the literature is produced. The frequent problem with working with area studies is that certain trajectories of research can perpetuate misreadings or appropriative readings of texts, because of the inadequate exposure the scholars in these countries have to new critical and cultural developments in the country or nation whose culture is being studied. I myself have encountered research done in India on Aboriginal Australian and Canadian writing that is several years behind the new directions taken in these countries, so that what is being done in India in many instances is derivative, or worse, culturally insensitive, vague research in area studies. Even when one’s research is a reflection of the guidance and directions provided by Aboriginal scholars or culturally knowledgeable scholars of Aboriginal studies, one must be self-reflexive, asking the questions that Arnold Krupat has asked of his own theoretical formulation of ‘ethnocriticism’ as a reading strategy for Native American cultures:

…inasmuch as the conceptual categories necessary to ethnocriticism - culture, history, imperialism, anthropology, literature, interdisciplinarity, even the frontier—are Western categories, the objection may be raised that ethnocriticism is itself no more than yet another form of imperialism, this time of a discursive and epistemological kind….

According to Elaine Jahner, critics need to be sensitive to the fact that conventional approaches and vocabulary are ‘as likely to obscure as to illuminate both the form and the content of Native literature, oral or written.’ Emma LaRocque sounds a warning note to cross-cultural researchers such as myself:

Even as a growing number of scholars are finally taking… (a) “cross-cultural” approach, Native peoples are in various phases of decolonizing. For many academics cross-cultural means their ‘academic’ right to use Native material in the advancement of (their) research and theory without that translating into bringing Aboriginal praxis in their pedagogy…. To Native peoples, cross-cultural means having the “inherent right” to practice and protect their Aboriginality. Decolonization demands having to define and protect more closely their identities (languages, literatures, among other things) and what is left of their lands and resources.

It is for this reason that one has to be constantly sensitive to the extent to which one’s reading frameworks are, or can be, appropriative, while at the same time one cannot be locked in a creative and intellectual paralysis, or a refusal to engage with texts because of one’s being a cultural ‘outsider’. The persistence of colonial power relationships in the production of academic knowledge prompts Patrick Wolfe to urge non-Aboriginal scholars to ‘speak when you’re spoken to.’ On the other hand, Aboriginal scholar Marcia Langton has described the unwillingness of non-Aboriginal scholars to engage in critical dialogue as racist. Avoiding any engagement with Aboriginal literatures does not serve any purpose except to foreclose dialogue. As David Hollinsworth puts it, ‘to suggest an innocence earned by abstinence is naïve and probably hypocritical.’ Langton invites crosscultural dialogue by suggesting the idea of Aboriginality as:

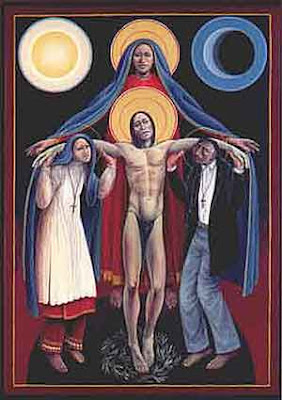

a field of intersubjectivity in that it is remade over and over again in a process of dialogue, of imagination, of representation and interpretation. Both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people create ‘Aboriginalities’…in the infinite array of intercultural experiences.

Louis Owens, drawing on Bakhtinian notions of the dialogic, asks if theory can ‘illuminate transcultural zones in such a way that such “dialogically agitated space” becomes a matrix within which communication and comprehension are indeed multidirectional and multi-reflexive.’ The first chapter explores the issues of ‘essential difference,’ separatism and sovereignty as well as the possibilities of decolonizing readings of Aboriginal literature that locate the text, the critic, the author and his/her world within this field of intersubjectivity.

At a fundamental level, the issue of cross-cultural reading raises the question of how one culture perceives another, and how meanings are exchanged. In considering the problem of cross-cultural interpretation, Elaine Jahner observes that non-Native scholars or for that matter, all scholars have to rely on ethnological information at various times to interpret symbols and metaphors in Aboriginal texts in order to fully explore their relevance to the themes being explored. Emma LaRocque acknowledges that a balance needs to be maintained between ‘too much ethnographication’ and the erasing of ‘real cultural differences’, calling the process a convoluted negotiation between mercurial ‘siamese twins’.

Kristina Fagan of the Labrador Metis nation suggests five different ways in which an appropriate level of cultural specificity might be achieved in the context of Aboriginal writing. The first is an author-centric approach, involving an extensive study of the influences, styles, etc. of the authors. Fagan suggests that a study of native traditions and movements as well, and suggests that this be specific to the culture of specific peoples, such as the Cree culture for reading Cree texts. Also, she suggests taking into consideration new traditions that may be arising – e.g. in the Native writers’ community in Toronto. The third aspect is the study of the languages of the writers and how the language affects those texts. Fagan suggests that even when native writers do not know their languages, they are still informed politically and aesthetically by their ancestral links. The need to interact with communities as sources of theories and not objects needs to be done by scholars working to record forms of Indigenous knowledge. Finally, Fagan focuses on understanding reader reception as a key aspect of research, for example the differences in response between the literary critic and the general reader. In my research on Nyoongar and Ojibwe writing, I have tried to follow the guidelines set by Fagan, though for reasons stated earlier, I have not been able to focus on the languages of the writers apart from English.

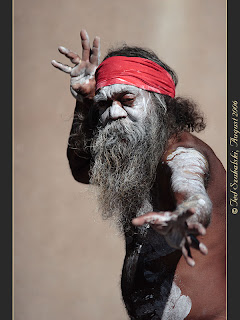

In order to develop a culturally sensitive cross-cultural reading framework, Ojibwe scholar Armand Ruffo suggests a process of cultural immersion and engagement over a long period of time with the dynamic and changing cultural contexts out of which Aboriginal literature is written. In this, there is much that is common in terms of the approach adopted by the researcher in ethnography and in literary studies. But literary studies perhaps needs to develop a research ethics similar to the one being evolved in the post-colonial social sciences regarding Aboriginal studies. This might seem unusual since the autonomy of the printed/recorded text is considered important in the western academy. Unlike the human subject, once the printed text/performance text is published, it is available for anyone who reads/hears/sees it. In my own work, I was not sure, for instance, of how the retrieval of Aboriginal voices or acts of resistance from old colonial textual records might hold up from the point of view of research ethics. To what extent would the use of colonial texts as sources holding traces of the voices of informants, as it were, hold up to the concept of accountability to the community being studied? When certain knowledges and epistemologies are the intellectual property of communities, the approach suggested by Linda Tuhiwai Smith becomes a viable solution in the humanities as well: the development of collaborative research where possible, with the acknowledgement of Aboriginal intellectual leadership or guidance, and a shift in emphasis to the theoretical and critical writing of Aboriginal scholars.

To merely force narratives by Aboriginal authors into established reading frameworks would be to inflict epistemic violence upon them.